† Corresponding author. E-mail:

Recently, the bound state solutions of a confined Klein-Gordon particle under the mixed scalar-vector generalized symmetric Woods-Saxon potential in one spatial dimension have been investigated. The obtained results reveal that in the spin symmetric limit discrete spectrum exists, while in the pseudo-spin symmetric limit it does not. In this manuscript, new insights and information are given by employing an analogy of the variational principle. The role of the difference of the magnitudes of the vector and scalar potential energies, namely the differentiation parameter, on the energy spectrum is examined. It is observed that the differentiation parameter determines the measure of the energy spectrum density by modifying the confined particleʼs mass-energy in addition to narrowing the spectrum interval length.

In nuclear physics, the spin symmetry (SS) and pseudopsin symmetry (PSS) concepts, originally postulated by Smith et al.[1] and Bell et al.,[2] were widely used to explain the nuclear structure dynamical phenomena.[3–7] The basics of these symmetries were explored comprehensively and the conclusion was that they depended on the existence of vector, Vv, and scalar, Vs, potential energies.[8–10] In 1997, Ginocchio revealed that PSS and SS occur with an attractive scalar and a repulsive vector potential energies that satisfy

The Dirac equation (DE) was investigated by using various potential energies in the SS and PSS limits. For instance in the SS limit, Wei et al. obtained an approximate analytic bound state solution of the DE by employing the Manning-Rosen potential,[11] the deformed generalized Pöschl-Teller potential[12] energies. Furthermore, in the same limit, they proposed a novel algebraic method to obtain the bound state solution of the DE with the second Pöschl-Teller potential energy.[13] In their other work, they examined the symmetrical well potential energy solutions in the DE within the exact SS limit.[14] They contributed the field with important papers in the PSS limit too. For instance, they discussed an algebraic approach in the DE for the modified Pöschl-Teller potential energy.[15] Moreover, they applied the Pekeris-type approximation to the pseudo-centrifugal term and investigated the bound state solutions in the DE for Manning-Rosen potential[16] and modified Rosen-Morse potential[17] energies.

Another relativistic equation, Klein-Gordon equation (KGE), also has been the subject of many scientific investigations in the SS and PSS limits. Ma et al. studied the D-dimensional KGE with a Coulomb potential in addition to a scalar potential.[18] Dong et al. obtained the exact bound state solution of the KGE with a ring-shaped potential in the SS limit.[19] Hassanabadi et al. studied the radial KGE for an Eckart and modified Hylleraas potential energy in D dimensions by using supersymmetric quantum mechanics technique.[20] In another paper, Hassanabadi et al. sought solutions of bound and scattering states on the Pösch-Teller potential energy in the KGE in the SS limit.[21] In the same year, Hassanabadi et al. examined the KGE with vector and scalar Woods-Saxon potential (WSP) energy and presented the scattering case solutions in terms of hypergeometric functions.[22] Only a while ago, Sargolzaeipor et al. extended the KGE in the presence of an Aharonov-Bohm magnetic field for the Cornell potential. Then, they introduced superstatistics in deformed formalism and derived the effective Boltzmann factor with modified Dirac delta distribution.[23]

Recently, we examined the scattering and bound state solutions of the KGE under the generalized symmetric Woods-Saxon potential (GSWSP) energy in the SS and PSS limits.[24–25] We observed that in the scattering case, the solutions existed in the SS and PSS limits.[24] In the bound state case, unlike the scattering case, bound state solutions existed only in the SS limit.[25]

GSWSP energy is the generalization of the well-known WSP energy[26] by introducing surface interaction terms,[27] and has been investigated in many research articles.[28–46] In one spatial dimension, it is given in the form of

On the other hand, in classical mechanics, an instantaneous configuration of a system is described by N generalized coordinates. A set of the generalized coordinates that is composed of both the coordinates and their respective momenta is represented with a point in the phase space. The development of the system over time is expressed by the motion of the point in the configuration space. Consequently, the motion of the system between any two distinct times is defined by the trajectory (N-dimensional curve) in the configuration space. Note that, the resultant curve in the configuration space is called “the configuration space trajectory” and it should not be interpreted as the real trajectory of any particle.

In general, in a configuration space there is an infinite number of configuration space trajectories between two points. All physical systems determine their configuration space trajectory by the Hamiltonʼs principle. Hamiltonʼs principle states that the true evaluation of a system between the initial and final points in the configuration space is described by that configuration space trajectory (among infinite number of all possible configuration space trajectories), along which the action functional has a stationary point.

The Hamiltonʼs principle, sometimes called the variational principle, has a wide usage in physics, not only in classical mechanics but also, in the theory of relativity, statistical mechanics, quantum field theory, etc.[47–48]

In this paper, our main motivation is to investigate the role of the

Note that, it is a very well known fact that the differentiation parameter is equal to zero in finite range potential wells.[49] This value corresponds to configurational space trajectory in the language of the variational approach.

We construct the paper as follows. In Sec.

We start with the KGE in the SS limit[25]

In a bound state problem, the boundary condition predicts that the particleʼs wave function has to vanish exponentially outside the well. This condition is satisfied if and only if, μ is a real number, whereas, ν is an imaginary number. We assign these constraints on the wave numbers defined in Eqs. (

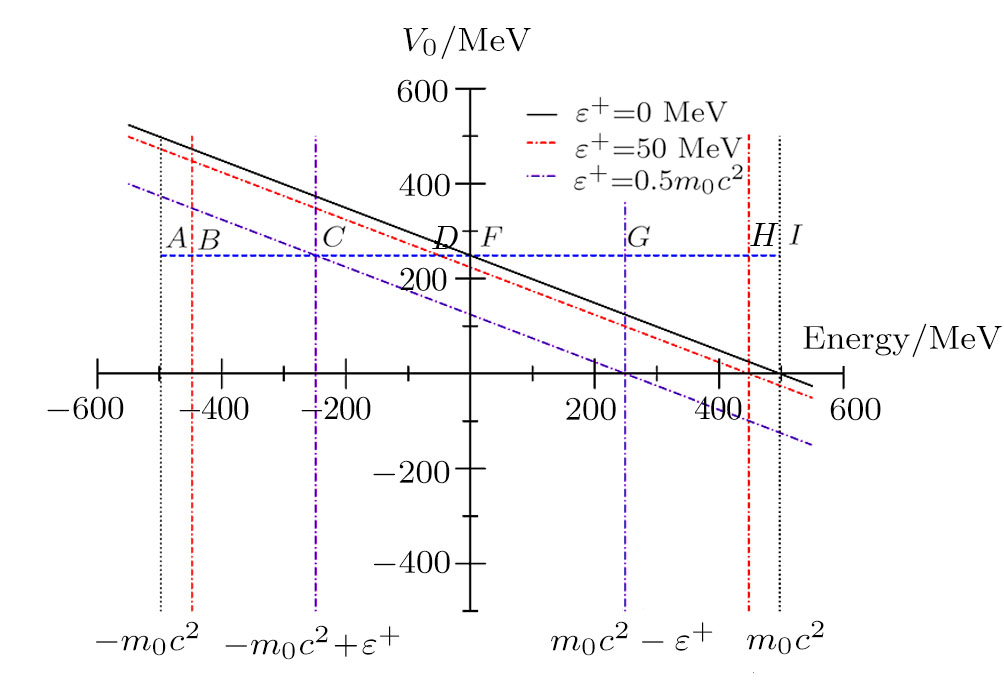

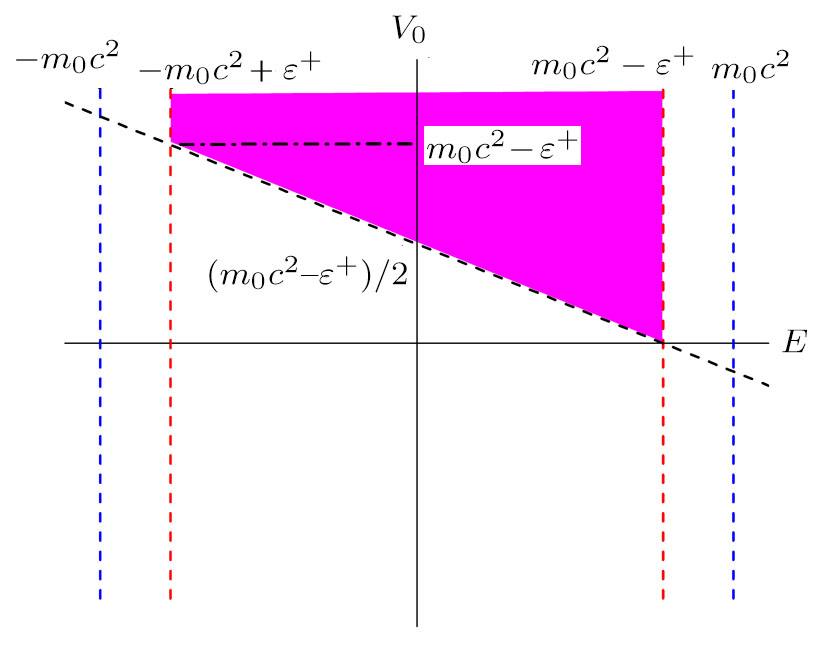

We investigate these conditions comprehensively in order to comprehend the crucial role of the differentiation parameter. In Fig.

| Fig. 1. Possible energy eigenvalue region for a confined particle in SS limit. Potential well depth parameter plays a crucial role in order to have positive and/or negative eigenvalues. |

We observe that the first constraint, given in Eq. (

The second constraint, given in Eq. (

Before we apply the continuity conditions, we examine the behavior of wave functions at positive and negative infinities. We find

If the potential energy has finite values, the continuity condition of the derivative of the wave function is accompanied by the condition of the continuity of the wave function. Therefore, in this study at the critical point x = 0, the wave function and its derivative should be equal to each other in the positive and negative regions.

After simple and straightforward calculations we obtain two equations that correspond to the continuity of the wave function

We use the continuity conditions, derived in Eqs. (

We obtain the even subset of the energy spectrum,

On the other hand, we establish the odd subset of the energy spectrum,

In this section we employ the NR numerical methods. We assume that the confined particle in the GSWSP energy well is a neutral Kaon. Note that its rest mass energy is

To calculate the energy spectra at various values of differentiation parameter, we use the equations obtained in Eqs. (

| Table 1.

Energy spectra for different values of the differentiation parameter for the repulsive surface interaction case. Note that all calculated eigenvalues and |

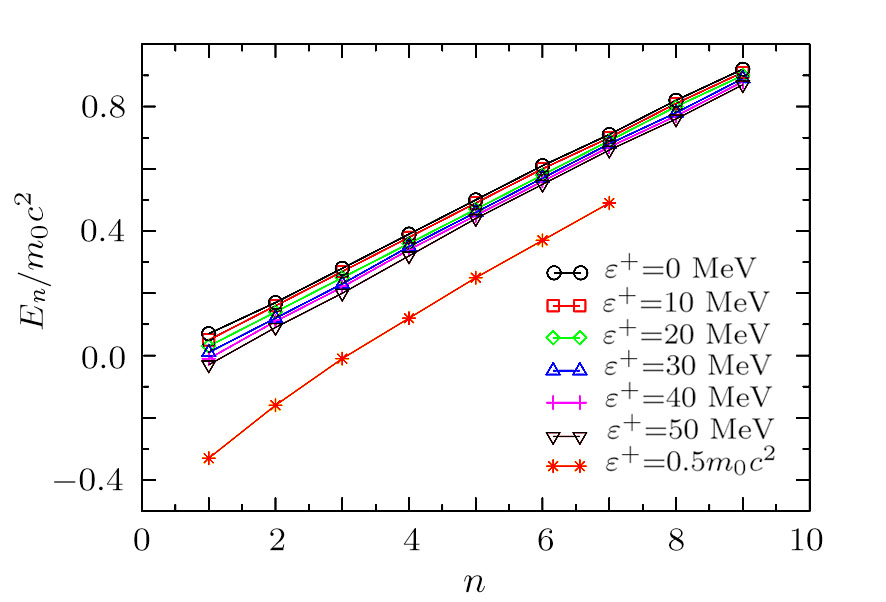

In Fig.

In the case of bound state problems, the depth parameter of the potential energy well in which the bound particle is located is initially determined and is constant throughout the problem. The increase of the differentiation parameter plays the role of the shift of the energy interval, due to the conditions that are given in Eq. (

Next, we assign an extreme value to the differentiation parameter. When the differentiation parameter is equal to

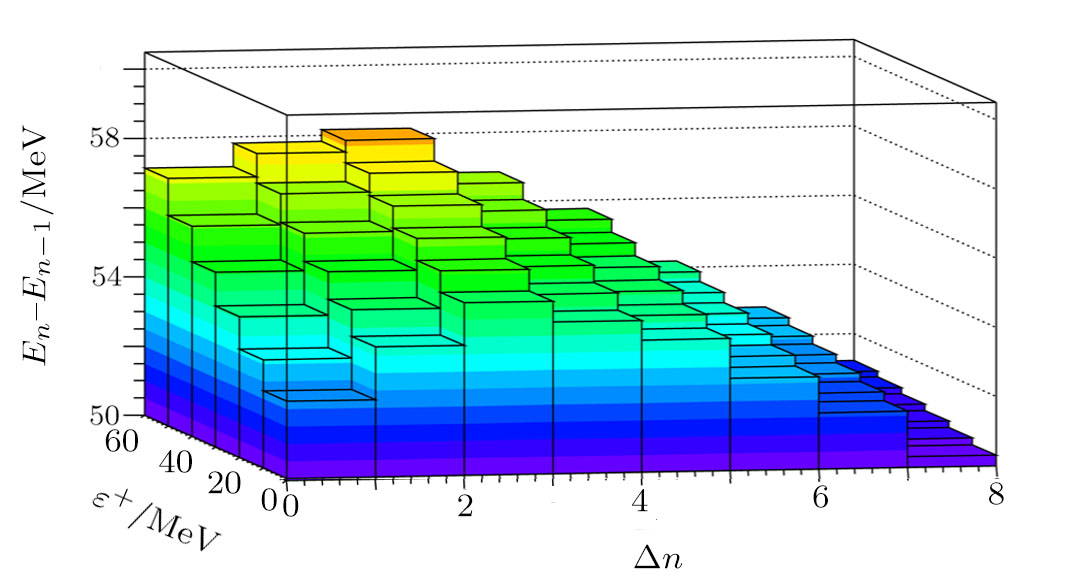

Finally, in Fig.

In this subsection, we employ the NR method to solve Eqs. (

| Table 2.

Energy spectra for different values of the differentiation parameter for attractive surface forces. Note that all calculated energies and |

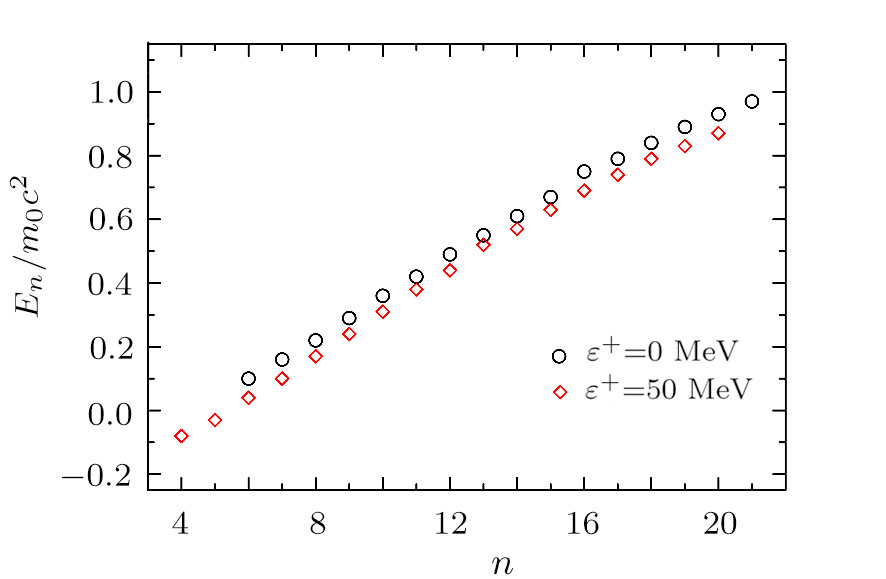

In Fig.

In this manuscript, we investigate the role of the differentiation parameter on the solution of the KGE in the SS limit by arising a novel analogy of the variational method. We examine the bound state conditions under the GSWSP energy with the presence of the differentiation parameter. Then, we discuss the continuity condition and quantization scheme. We observe that one of the role of the differentiation parameter is to modify the confined particleʼs mass-energy, hence to narrow the spectrum interval length. In order to obtain numerical results, we use a neutral Kaon confinement in a GSWSP energy well. In the presence of differentiation parameters, we obtain various energy spectra for the repulsive and attractive surface effect cases. As consequences of discussions that have been done, we conclude that the differentiation parameter plays the role of to be a measure of the density of the eigenvalues. Furthermore, we show that higher values of differentiation parameter correspond to a greater step size in the spectrum compared to that of its lower values, in both repulsive and attractive surface effects.

The author is indebted to Prof. M. Hortaçsu and Prof. J. Kříž for the proof reading. The author thanks to the reviewers for their kind recommendations that lead several improvements in the article.

| [1] | |

| [2] | |

| [3] | |

| [4] | |

| [5] | |

| [6] | |

| [7] | |

| [8] | |

| [9] | |

| [10] | |

| [11] | |

| [12] | |

| [13] | |

| [14] | |

| [15] | |

| [16] | |

| [17] | |

| [18] | |

| [19] | |

| [20] | |

| [21] | |

| [22] | |

| [23] | |

| [24] | |

| [25] | |

| [26] | |

| [27] | |

| [28] | |

| [29] | |

| [30] | |

| [31] | |

| [32] | |

| [33] | |

| [34] | |

| [35] | |

| [36] | |

| [37] | |

| [38] | |

| [39] | |

| [40] | |

| [41] | |

| [42] | |

| [43] | |

| [44] | |

| [45] | |

| [46] | |

| [47] | |

| [48] | |

| [49] | |

| [50] |