自 20 世纪初发现镉 (Cd) 以来,Cd 被广泛应用于电镀工业、化工业、电子业和核工业等领域,相当数量的 Cd 被排入环境,引起全球性土壤 Cd 污染[1]。如,美国加州南部农业用地土壤 Cd 含量为 0.005~2 mg/kg[2];英国、法国污染区土壤 Cd 含量分别为 1.5~5.7 mg/kg[3]和 3.1~31.4 mg/kg[4];澳大利亚、尼日利亚和印度的污染区土壤 Cd 含量分别为 1.0~9.8 mg/kg[5]、0.41~17.23 mg/kg[6]和 0.55~8.85 mg/kg[7]。我国土壤 Cd 污染形势也极为严峻。20 世纪末,我国土壤 Cd 污染面积已达 13000 hm2,涉及 11 个省市的 25 个地区[8]。2014 年全国土壤污染调查公报显示,我国土壤中 Cd 的点位超标率已高达 7.0%,中轻度污染达 1.3%。耕地中 Cd 的点位超标率则更高,为调查污染物之首[9]。近 10 年来的文献资料也表明我国耕地 Cd 污染形势严峻[10]。如我国南部土壤 Cd 含量为 0.121~3.153 mg/kg[11];珠江口农业用地土壤 Cd 含量达 0.099~3.778 mg/kg[12];北方 30 个污灌区土壤 Cd 含量为 0.05~2.23 mg/kg[13]。我国作为一个耕地资源短缺的国家,大面积的中、轻和轻微 Cd 污染耕地仍用于农业生产。耕作土壤中的 Cd 易被农作物根系吸收且易在体内积累,直接影响作物的生长和发育,造成农作物减产及 Cd 的积累[14]。作物中的 Cd 还将通过食物链进入人体,危害人类健康。因此,寻找合适的方法以缓解 Cd 对作物的生长胁迫并降低污染土壤中作物体内 Cd 的含量尤为重要。通过源头控制,即通过修复污染土壤以减轻农作物对重金属的积累是最常见的方法之一[15]。然而,这些方法虽能减少土壤重金属污染,但具有较大的局限性。例如,土壤淋洗法不适用于粘质土壤,且提取剂选择不当易破坏土壤结构,甚至造成土壤的二次污染[16];土壤固化技术中,常用的固化剂如粘土、水泥、沸石、矿物及磷酸盐[17–18]因其高成本而不适合大面积土壤的修复[19];植物修复技术存在周期长、修复效率较低的问题[20]。因此,寻找操作简单且高效的方法以减轻 Cd 对植物的毒害并降低作物中 Cd 含量仍然迫切。

氮元素是作物必需的营养物质之一。氮肥的施用也是非常重要的农业措施[21]。以往研究发现,植物在吸收铵态氮时会导致 H+ 释放至土壤中,使土壤 pH 值降低[22],从而增强土壤 Cd 的生物有效性。相反,施加硝态氮肥可促进植物体内 OH– 的释放,以维持土壤酸碱度的平衡,从而降低了土壤 Cd 的有效性。该观点在 Florijn 等[23]和 Zaccheo 等[24]的土培试验,以及 Eriksson[25]、Willaert 和 Verloo[26]和 Liu 等[27]的水培试验中得到证实。然而,也有一些研究发现了相反的现象:施用硫酸铵的水稻,其抗 Cd 胁迫能力高于硝酸钙[28];硝态氮处理下超积累植物遏蓝菜地上部 Cd 含量是铵态氮处理下的 2 倍[29];施用硝态氮的东南景天中的 Cd 含量也高于铵态氮处理[30]。这些研究认为施加硝态氮肥可促进 Cd 的协同运输,从而使植株长势较差且积累较多的 Cd[31–32]。虽然上述研究的结论并不一致,但均表明了氮肥的种类对植物抗 Cd 胁迫及 Cd 在植物体内积累的能力具有较大的影响。这些研究结论的不一致可能与土壤特性尤其是土壤缓冲性有关[33]。随着土壤酸化的日益严峻,南方酸性土壤的缓冲性弱的问题受到了广泛关注[34]。研究氮肥形态不同对缓冲性较差的 Cd 污染土壤中植株生长及 Cd 积累的影响具有理论实践意义。此外,上述已报道的研究均以谷类作物或超积累植物为研究对象,而关于这些氮肥对 Cd 污染蔬菜的影响研究未见报道。事实上,来源于蔬菜的 Cd 摄入比重极高,可占 Cd 摄入量的 70%~90%[35]。Shentu 等[36]采用土培试验研究了 Cd 0~7 mg/kg 对小白菜、番茄和萝卜生长和 Cd 吸收的影响;Liu 等[37]的大白菜土培试验选用了 Cd 1.0、2.5 和 5 mg/kg 处理浓度;Chen 等[38]则设置 Cd 3、6、9、12 和 24 mg/kg 浓度处理,探明不同程度 Cd 污染土壤对大白菜和芥菜的生长的影响;杨芸等[39]研究了 Cd 10 mg/kg 处理浓度下番茄生长的情况。结合北方 3 个区域 (东北、黄淮海、西北地区) 和南方 4 个区域 (华中、西南、华东、华南地区) 远离城郊的未受到工业“三废”、汽车尾气等污染的共 503 个典型农村菜田耕层土壤样品的调查数据,即未污染区土壤 Cd 含量达 0.03~3.64 mg/kg[40],并适当考虑菜田 Cd 污染的普遍性,本研究拟通过 1、3 和 5 mg/kg Cd 的土壤盆栽试验,分析对比几种在中国施用较为普遍的速效氮肥 (铵态、硝态、硝铵复合和酰胺态氮肥) 对小白菜生长影响和 Cd 含量的差异,为重金属轻微污染土壤的利用及食品安全提供施肥理论依据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 供试土壤和作物盆栽作物为小白菜 (Brassica chinensis L., 上海青)。供试土壤取自浙江杭州近郊区菜园土壤 (0—40 cm)。供试土壤经风干,过 4 mm 尼龙筛充分摇匀。土壤 pH、电导率、阳离子交换量、有机质、铵态氮和硝态氮按鲍士旦[41]的方法测定。土壤总 Cd 含量按鲁如坤[42]的方法将土壤用 4∶1∶2 的 HNO3/HClO4/HF 的强酸消解后用原子吸收仪测定。土壤基本理化性质:pH 7.2、电导率 0.7 mS/cm、铵态氮 2.5 mg/kg、硝态氮 13.4 mg/kg、有机质 2.5 g/kg、阳离子交换量 7.9 cmol/kg、总 Cd 含量 0.23 mg/kg。

1.2 盆栽处理供试土壤为人工模拟 Cd 污染土壤,设 Cd 污染水平 1、3 和 5 mg/kg 土,将处理需要的 Cd 量以 CdCl2 溶液的形式先与少量土壤充分混合均匀,再与剩余土壤混合均匀,放置老化 2 个月后用于盆栽试验[36, 43]。设 4 个氮肥处理,分别为铵态氮[(NH4)2SO4]、硝态氮 (NaNO3)、硝铵 (1∶1) 和尿素,氮肥施用量均为 N 400 mg/kg,每个处理重复 3 次。盆栽试验在自然通风条件下进行,平均气温为 9℃,相同大小的小白菜种子经 0.1% H2O2 表面消毒 20 min 后,用蒸馏水彻底冲洗,于无菌水中浸泡过夜。随后,转移至普通土壤中培养至发芽。当幼苗长至双叶龄 (大约播种后 20 d) 时,挑选长势一致的幼苗移栽至盆栽土壤中,每盆 4 株。生长过程中浇灌去离子水,保持土壤含水量于 60% 左右。移栽 70 d 后分析叶片光合速率,随后收获,称重,并测定各部位 Cd 含量。

1.3 测定指标及方法叶片光合速率测定:选取同一部位的完全展开叶片,用光合作用分析仪 (LI-6400 型,Li-COR 公司,美国) 测定。参数如下:普通叶室;红、蓝光源;光子通量密度 1200 μmol/(m2·s);叶片面积 4 cm2;叶室相对湿度 70%;CO2 浓度 424 μL/L。

小白菜组织 Cd 含量测定:用自来水冲去小白菜根系表面粘附的泥土,然后将根部浸于 20 mmol/L Na2-EDTA 溶液中保持 15 min 以去除吸附在根表面的 Cd[44]。用蒸馏水冲洗根部并迅速用吸水纸吸干后进行称重。将植物组织分装于信封中,置于烘箱内,于 105℃ 下杀青 30 min,70℃ 下烘干至恒重。对烘干的植物样品进行称重和研磨。研磨后的样品粉末用 HNO3/HCl(3∶1,v/v) 消煮至澄清,随后用原子吸收分光光度计 (ICE 3300 型,赛默飞世尔科技公司,美国) 测定[31]。

小白菜叶片丙二醛 (MDA) 含量和$\rm{O}_{\small 2}^{\overline {\,\cdot\,}} $产生速率测定:采用硫代巴比妥酸 (TBA) 比色法,于波长 532 nm、600 nm 和 450 nm 下进行测定[45]。小白菜叶片$\rm{O}_{\small 2}^{\overline {\,\cdot\,}} $产生速率通过添加氨基苯磺酸和 α-萘胺反应后于 530 nm 下测定[45]。

土壤有效态镉含量测定:按 GB/T 23739-2009 进行测定[46],称取 5.0 g 土壤于 100 mL 三角瓶内,加入 0.005 mol/L 二乙三胺五乙酸 (DTPA)–0.1mol/L 三乙醇胺 (TEA)–0.01 mol/L CaCl2 浸提液,25℃ 振荡 2 h。用 0.45 μm 的纤维素滤膜过滤浸提液,稀释后用原子吸收分光光度计测定。

1.4 数据统计与分析小白菜 Cd 耐受指数 (TICd) 按 Gill 等[47]的方法计算:

TICd(%)=1、3 或 5 mg/kg Cd 污染土壤中植物组织平均干重/0 mg/kg Cd 土壤中植物组织平均干重 × 100。

小白菜 Cd 转移系数 (TF) 按 Mattina 等[48]的方法计算:

TF = 小白菜目标组织 Cd 含量/小白菜起始组织 Cd 含量。

有效态镉含量测定重复 5 次,其余指标测定重复 3 次,所有图表用 Kyplot 软件绘制。图和表中的值为平均值及标准差,不同字母表示差异达 5% 显著水平。

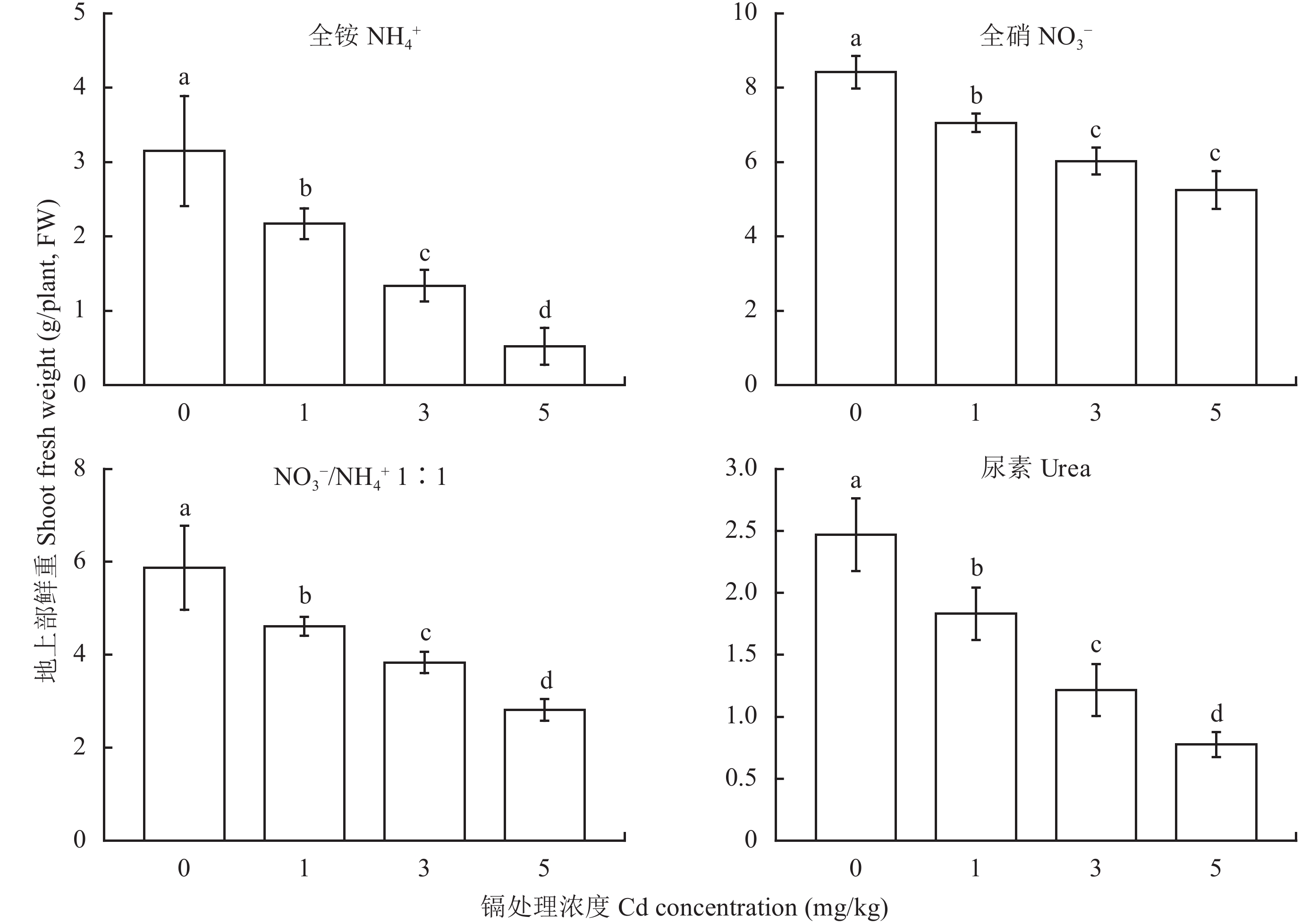

2 结果与分析 2.1 不同氮肥对 Cd污染土壤小白菜生长的影响如图 1 所示,随着土壤中镉浓度的增加,小白菜的生物量均出现了下降的趋势。与未添加 Cd 土壤的小白菜植株相比,Cd 污染水平为 1 mg/kg 时,施用铵态氮、硝态氮、硝铵 1∶1 和尿素的小白菜可食部分鲜重分别下降了 31%、16%、21% 和 26%;Cd 污染水平为 3 mg/kg 时,分别下降了 58%、28%、35% 和 39%;Cd 污染水平为 5 mg/kg 时,分别下降了 83%、38%、52% 和 69%。由此可见,施用硝态氮和硝铵比 1∶1 的氮肥时 Cd 对小白菜生长的抑制作用相对较小。

|

|

图1

镉污染土壤中施用不同氮肥小白菜的可食部分鲜重

Fig. 1

Fresh biomass of the edible part of pakchoi supplied with different N forms under different levels of Cd-contamination

|

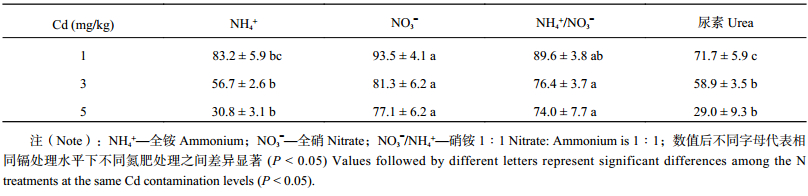

Cd 耐受系数 (TICd) 通常被用于反映植株抗 Cd 生长胁迫的能力。表 1 结果表明,随着 Cd 处理浓度的增加,所有氮肥处理下小白菜的 TICd 均出现了不同程度的降低。当 Cd 处理浓度为 1 mg/kg 时,全硝与硝铵 1∶1 处理间 TICd 差异不显著,但均高于全铵和尿素处理。Cd 处理浓度为 3 mg/kg 时,全硝和硝铵 1∶1 处理下小白菜的 TICd 分别比全铵和尿素处理高了约 30%~40%,达显著性水平。Cd 处理浓度为 5 mg/kg 时,全硝处理下小白菜的 TICd 与硝铵 1∶1 处理间的差异仍然未达显著水平,但分别是全铵和尿素处理的 2.5 和 2.7 倍。上述结果表明:全铵和尿素处理下 TICd 降幅远大于全硝和硝铵 1∶1 处理;与全铵和尿素处理相比,全硝和硝铵 1∶1 处理下的小白菜具有更强的 Cd 耐受能力。

| 表1 镉污染土壤中施用不同形态氮小白菜镉耐受系数 (TICd) Table 1 Cd tolerance index (TICd) of pakchoi in different N form supply under different Cd stress |

|

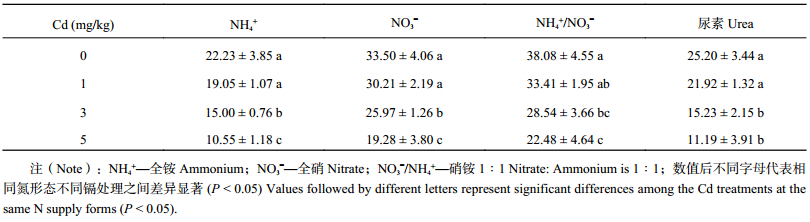

如表 2 所示,随着土壤 Cd 浓度的提高,4 个氮形态处理小白菜的光合作用速率均受到了严重的抑制。与对照相比,在 Cd 1 mg/kg 处理,施加铵态氮、硝态氮、硝铵 1∶1 和酰胺态氮的小白菜叶片光合作用速率分别下降了 14%、10%、12% 和 13%;Cd 3 mg/kg 处理的分别下降了 33%、22%、25% 和 40%;Cd 5 mg/kg 处理的分别下降了 53%、42%、41% 和 56%。施用铵态氮和酰胺态氮小白菜光合速率受到的抑制高于施用硝态氮和硝铵 1∶1 处理,并且该差异随着 Cd 浓度的提高而加大。

| 表2 土壤不同镉胁迫水平、施用不同形态氮小白菜叶片的光合速率[μmol/(m2·s)] Table 2 Photosynthetic rate of pakchoi supplied with different N forms under Cd stress levels |

|

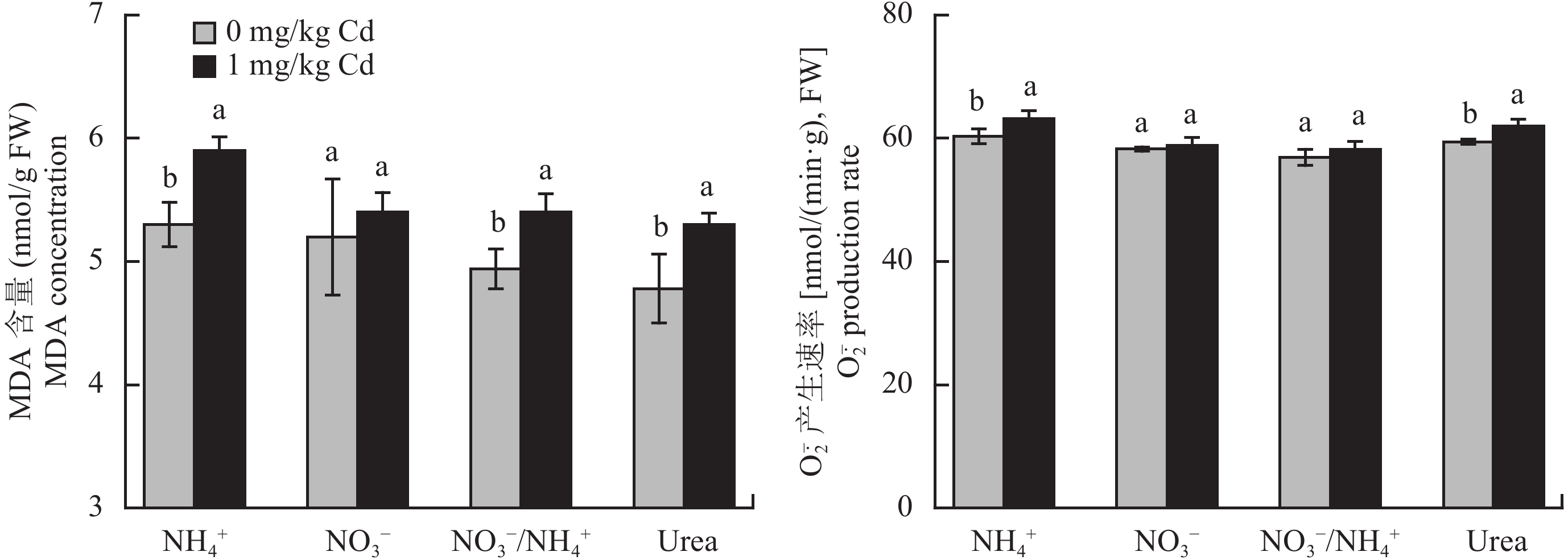

如图 2 所示,与未添加 Cd 对照相比,1 mg/kg Cd 污染土壤中施加铵态氮、硝态氮、硝铵 1∶1 和酰胺态氮的小白菜叶片 MDA 含量增加了 11%、4%、9% 和 11%;$\rm{O}_{\small 2}^{\overline {\,\cdot\,}} $产生速率增加了 5%、1%、2% 和 4%。硝态氮处理下 Cd 诱导的氧化胁迫未达显著水平,而铵态氮和酰胺态氮处理的小白菜叶片 MDA 含量和$\rm{O}_{\small 2}^{\overline {\,\cdot\,}} $产生速率受 Cd 污染影响显著。

|

|

图2

不同镉胁迫水平、施用不同形态氮小白菜叶片的 MDA 含量和$\rm{O}_{\small 2}^{\overline {\,\cdot\,}} $产生速率

Fig. 2

MDA concentrations and $\rm{O}_{\small 2}^{\overline {\,\cdot\,}} $ production rates in leaves of pakchoi supplied with different N forms under different Cd stress levels

|

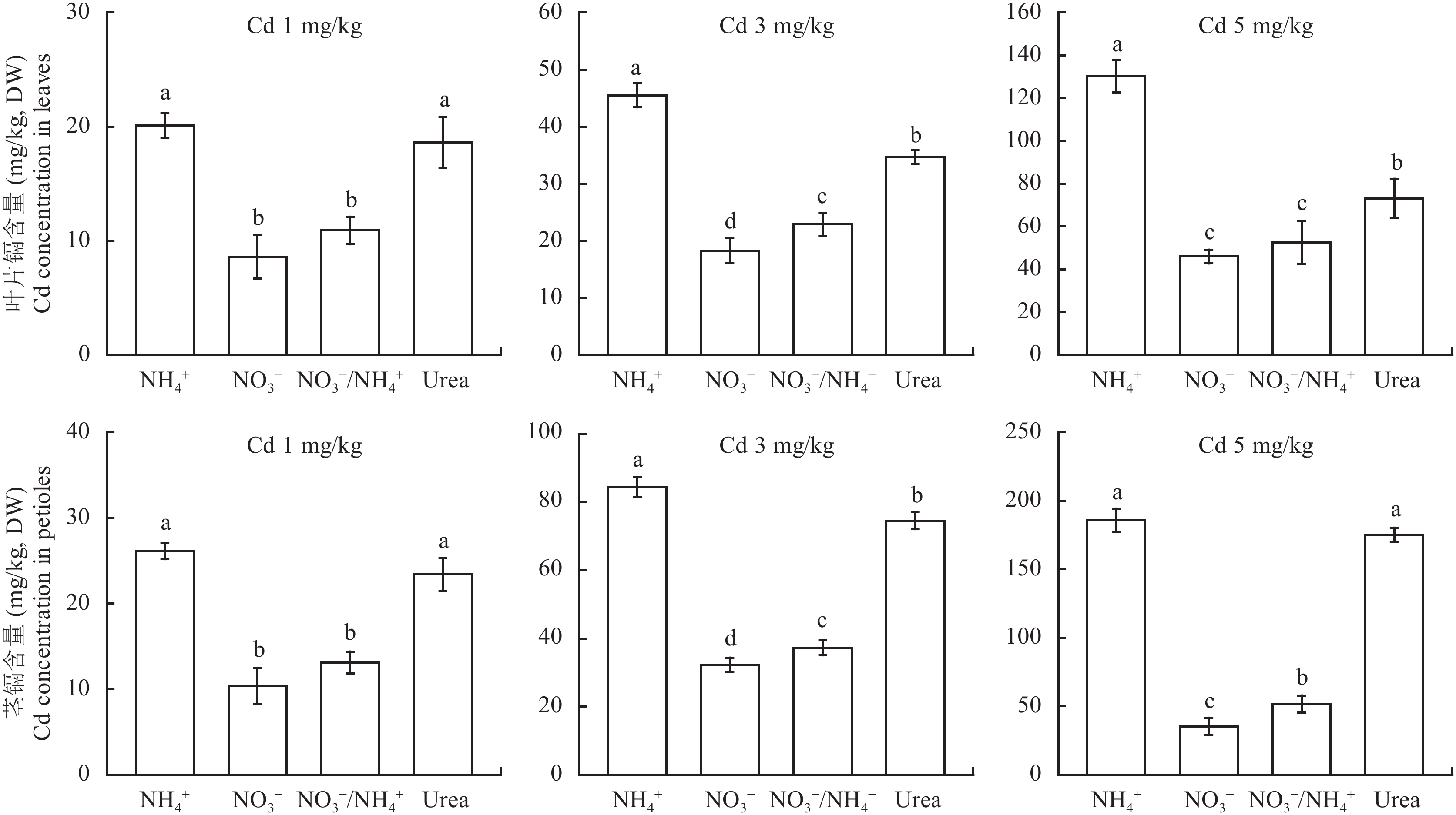

土壤 Cd 污染程度的增加,可使所有氮肥处理下的小白菜叶片和茎 Cd 含量成倍增加 (图 3)。然而,不同速效氮肥供应下小白菜体内 Cd 含量存在一定差异。于 1 mg/kg Cd 浓度下,全铵与尿素处理小白菜叶片和茎 Cd 含量无显著差异,但均显著高于全硝和硝铵复合处理,增幅可达 70%~150%。3 mg/kg 和 5 mg/kg Cd 处理下,不同形态氮肥处理小白菜 Cd 含量变化趋势较为接近,3 mg/kg Cd 浓度时,全铵、尿素和硝铵处理下小白菜体内 Cd 含量分别是全硝处理的 2.5、1.9 和 1.3 倍 (叶) 和 2.6、2.3 和 1.2 倍 (茎);5 mg/kg Cd 浓度时,则分别是全硝处理的 2.8、1.6 和 1.1 倍 (叶) 和 5.3、5.0 和 1.5 倍 (茎)。上述结果表明,全硝处理下的小白菜 Cd 含量最低,硝铵处理次之,全铵和尿素处理最高。并且,随着 Cd 处理浓度的增加,氮肥处理之间的差异也更为明显。

|

|

图3

不同镉胁迫水平和施用不同形态氮小白菜组织镉含量

Fig. 3

Cd concentrations in pakchoi supplied with different N forms under different Cd stress levels

|

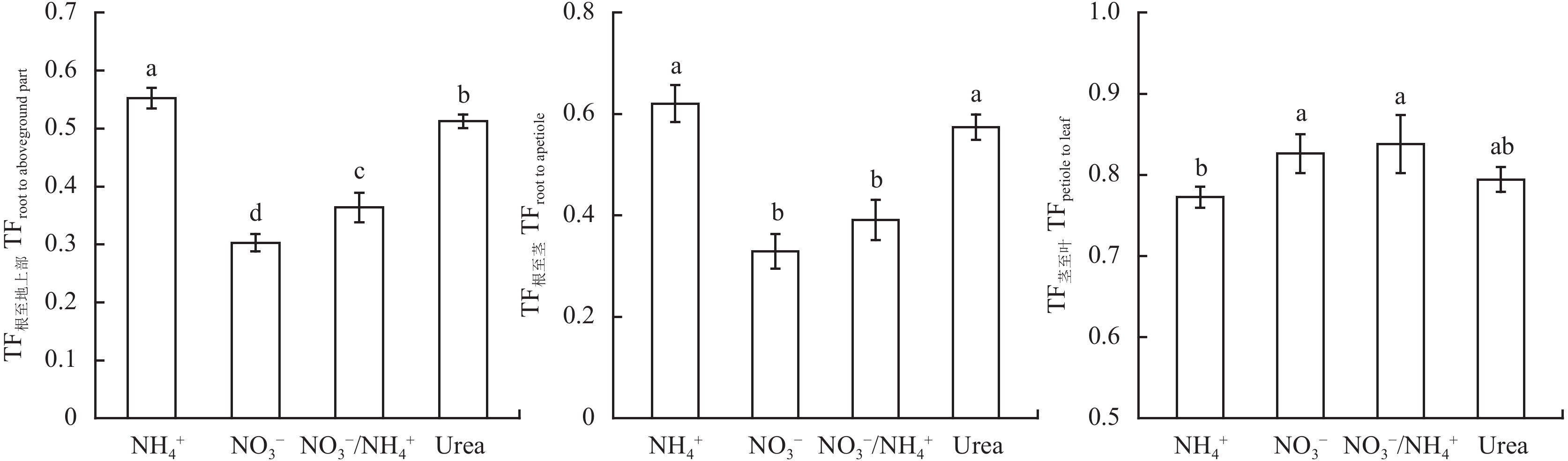

根据小白菜叶、茎和根中 Cd 的含量,可计算 Cd 转移系数 TF根至地上部、TF根至茎 和 TF茎至叶 用以研究植物体内 Cd 的分配情况。如图 4 所示,1 mg/kg Cd 土壤中,铵态氮处理的小白菜有着最大的 TF根至地上部,比硝态氮、硝铵 1∶1 和酰胺态处理分别增加了 82%、52% 和 8%,说明施加铵态氮的小白菜中 Cd 从根转移至地上部的能力最强。铵态氮及酰胺态氮处理下小白菜的 TF根至茎 无明显差异,约为硝态氮和硝铵 1∶1 处理的 1.5~1.9 倍,说明铵态氮和酰胺态氮显著提高了小白菜中 Cd 从根至茎的转运能力。硝态氮、硝铵 1∶1 和酰胺态氮处理下的 TF茎至叶 无显著差异,分别比铵态氮处理高了 7%、8% 和 3%,说明在硝态氮和硝铵 1∶1 处理下,进入小白菜地上部的 Cd 在植物体内更易向叶转运。

|

|

图4

1 mg/kg 镉胁迫水平下施用不同形态氮小白菜的镉转移系数

Fig. 4

TFs of Cd in pakchoi supplied with different N forms under 1 mg/kg Cd stress level

|

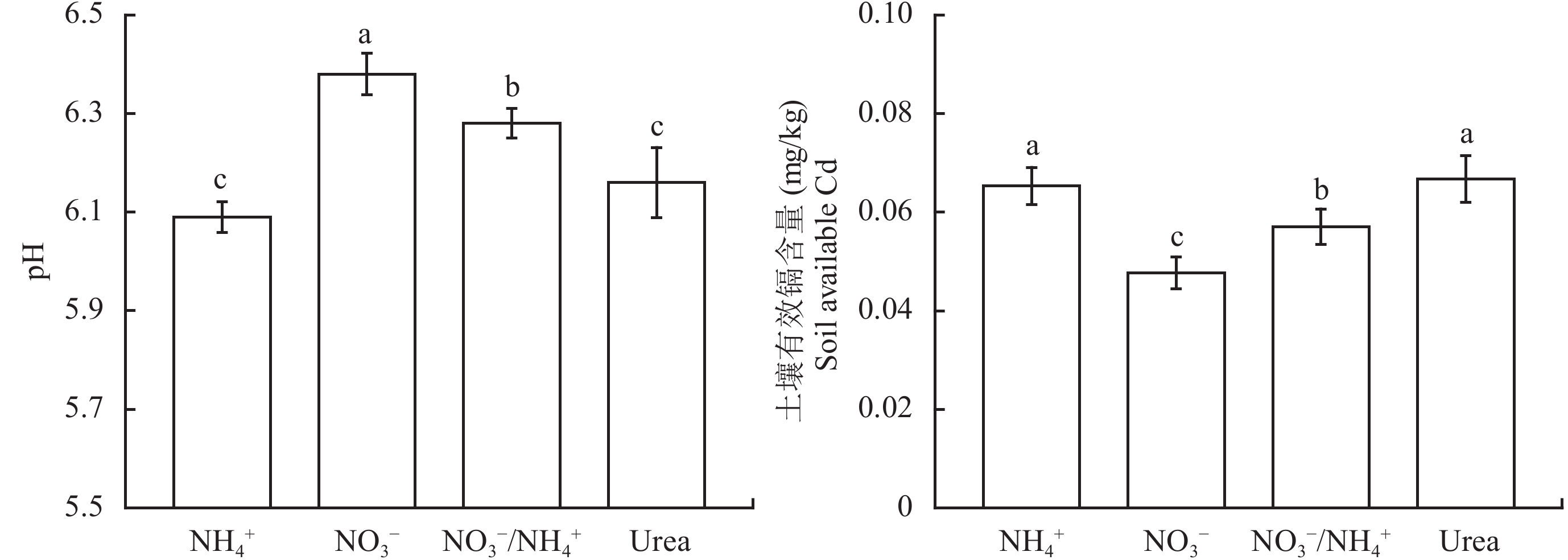

由图 5 可知,各氮肥处理之间土壤的 pH 差异显著。其中,全硝处理下土壤 pH 最高。袁波等[50]研究表明土壤 pH 对土壤有效态 Cd 含量影响较大,通常情况下呈负相关性。我们的结果也符合这一规律,即硝态氮处理下土壤有效态 Cd 含量最低,硝铵 1∶1 处理次之,酰胺态氮和铵态氮处理最高。

|

|

图5

1 mg/kg 镉胁迫下施用不同形态氮的土壤 pH 和有效态镉含量

Fig. 5

Soil pH values and available Cd contents affected by nitrogen forms under 1 mg/kg of Cd stress level

|

本研究的结果表明,Cd 会抑制小白菜的生长,引起生物量的下降。在土壤 Cd 处理浓度为 1、3 或 5 mg/kg 时,供应铵态氮和尿素的小白菜生物量减产高于供应硝态氮和硝铵 1∶1 处理 (图 1)。由耐受系数 TICd 值可知,全硝和硝铵处理下小白菜对 Cd 的耐性无显著差异,并均高于全铵和尿素处理 (表 1)。这些数据均说明了 Cd 污染土壤中,施用硝态氮肥时 Cd 对小白菜的生长胁迫低于全铵及尿素处理。虽然硝铵 1∶1 处理下的小白菜的 Cd 耐受性与全硝处理无显著性差异,但该处理下小白菜的生物量仍低于全硝处理,这可能与小白菜是一种喜硝作物有关[51]。因此,在本供试土壤条件下,综合考虑 Cd 对植株生长的抑制及小白菜喜硝的特点,全硝供氮形式为最优选。众所周知,Cd 对植物光合作用的抑制引起植物生物量的下降,被认为是 Cd 引起植物生长胁迫的重要成因之一[52–53]。本研究结果表明,硝氮处理下小白菜叶片的光合性能因 Cd 引起的下降显著小于铵氮和尿素处理 (表 2)。这可能是导致硝氮处理下小白菜生物量下降幅度相较于铵肥和尿素处理低的可能原因之一。另一方面,Cd 胁迫能诱导植物体内氧化胁迫的发生[54]。本研究表明,Cd 胁迫均导致了各种供氮处理下小白菜叶片中 O2– 的累积 (图 2)。其中,铵氮和尿素处理下小白菜叶片 O2– 的积累更为显著。随着活性氧的积累,细胞膜脂质过氧化加剧,组织或器官脂质过氧化反应将产生 MDA[55–56]。本研究也显示,全铵和尿素处理下小白菜叶片 MDA 积累幅度也超过了全硝和硝铵复合处理。因此,我们认为全铵和尿素处理下 Cd 引起的氧化胁迫大于硝肥处理也可能是导致硝肥处理下小白菜生物量下降幅度相较于全铵和尿素处理低的原因。

由于对食物的大量需求,中国仍有大面积受 Cd 污染的土壤用于农业生产[57]。土壤 Cd 污染引起的农产品 Cd 积累已成为农业生产及食品安全的严峻问题。由于中国大多数地区土壤的平均肥力不高,氮素不易在土壤中积累,因此氮肥在农业中有着广泛的应用。本研究发现,与硝氮处理的小白菜相比,Cd 污染土壤中施用全铵和尿素的小白菜叶和茎中 Cd 含量更高 (图 3)。该现象与大多数观点一致,即土壤施用铵态氮肥会增加 Cd 在植物体内的积累[25, 58–59]。引起上述现象的机制可能与植物对氮的吸收引起缓冲性较差土壤的 pH 变化有关。如,土壤中的 H+伴随着硝酸根离子的吸收而进入植物体,导致土壤 pH 的增加。而当铵根离子被植物体吸收时,植物体内的 H+则会释放到土壤中,造成土壤酸化[23, 60–61]。土壤 pH 的变化,又会通过离子交换作用影响重金属从交换态或土壤胶体中的解吸从而影响土壤 Cd 的植物有效性[62–64]。因此,氮肥可改变土壤中 Cd 的有效性及其在植物中的积累[65]。本试验通过测定各处理下土壤的 pH 和有效态 Cd 也证实,施用全铵、硝铵复合及尿素的土壤 pH 均低于全硝处理,有效态 Cd 含量则高于全硝处理 (图 5)。全硝处理下较高的土壤 pH 和较低的有效态 Cd 可能是该处理下小白菜体内 Cd 含量最低的原因。处理间 pH 和 Cd 有效性的差异也可从侧面解释以下现象:1) 全铵处理下,土壤 Cd 有效性高,Cd 由根向茎的转运能力强 (图 4);2) 硝铵复合处理下土壤 Cd 有效性略高于全硝处理,施用硝铵复合肥小白菜的 Cd 含量低于施用铵态氮肥和尿素,但略高于全硝氮肥 (图 3 和图 5);3) 土壤中施用尿素后虽会因尿酶的水解而导致土壤 pH 的升高,但长期存留在土壤中的尿素会转化为铵根从而引起土壤 pH 的降低[26]。因而,尿素处理下 Cd 污染对小白菜的生长抑制及 Cd 含量的影响情况近似全铵处理 (图 1、图 3 和图 4)。另外,最新的水培研究表明硝态氮能促进 Cd 共运至植物体内[31, 66]。该结论从某种程度上也为本研究中硝态氮处理 TF茎至叶 高于铵和尿素处理给予了一定的解释 (图 4)。

综上,硝态氮肥更有利于维持土壤 pH 和低的有效态 Cd 水平,可缓解 Cd 诱导的光合抑制和氧化胁迫,减轻 Cd 对小白菜的生长胁迫,并有利于降低作物体内 Cd 的含量。因此,在叶菜类蔬菜的氮肥管理中,建议在缓冲性较差的 Cd 污染土壤中优选硝态氮肥。另外,今后还应该进一步选用不同特性的土壤 (尤其是缓冲性较好的土壤) 开展后续研究,以明确在不同土壤特性 Cd 污染条件下的氮肥施用方法。值得注意的是,本研究采用了人工模拟土壤,不能完全代表其他 Cd 污染水平的农田情况。因此,建议今后的研究选用长期轻微、轻度 Cd 污染农田土壤为供试对象,以获取更全面的信息。

| [1] |

李志涛, 王夏晖, 刘瑞平, 等. 耕地土壤镉污染管控对策研究[J].

环境与可持续发展, 2016, 41(2): 21–23.

Li Z T, Wang X H, Liu R P, et al. Control strategy research of cadmium pollution in cultivated soils[J]. Environment and Sustainable Development, 2016, 41(2): 21–23. |

| [2] | Holmgren G G S, Meyer M W, Chaney R L, Daniels R B. Cadmium, lead, zinc, copper, and nickel in agricultural soils of the United States of America[J]. Journal of Environmental Quality, 1993, 22(2): 335–348. |

| [3] | Han F X, Banin A, Su Y, et al. Industrial age anthropogenic inputs of heavy metals into the pedosphere[J]. The Science of Nature, 2002, 89(11): 497–504. DOI:10.1007/s00114-002-0373-4 |

| [4] | Roussel H, Waterlot C, Pelfrêne A, et al. Cd, Pb and Zn oral bioaccessibility of urban soils contaminated in the past by atmospheric emissions from two lead and zinc smelters[J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2010, 58(4): 945–954. DOI:10.1007/s00244-009-9425-5 |

| [5] | Tolyer M P, Mackay A K, Hudson-Edwards K A, Holz E. Soil Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn contaminants around Mount Isa city, Queensland, Australia: potential sources and risks to human health[J]. Applied Geochemistry, 2010, 25(6): 841–855. DOI:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2010.03.003 |

| [6] | Adelekan B A, Abegunde K D. Heavy metals contamination of soil and groundwater at automobile mechanic villages in Ibadan, Nigeria[J]. International Journal of Physical Sciences, 2011, 6(5): 1045–1058. |

| [7] | Sharma R K, Agrawal M, Marshall F. Heavy metal contamination of soil and vegetables in suburban areas of Varanasi, India[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2007, 66(2): 258–266. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.11.007 |

| [8] | Chen H M, Zheng C R, Tu C, Zhu Y G. Heavy metal pollution in soils in China: status and countermeasures[J]. A Journal of the Human Environment, 1999, 28(2): 130–134. |

| [9] |

环境保护部, 国土资源部. 全国土壤污染状况调查公报[EB/OL]. http://www.gov.cn/foot/2014-04/17/content_2661768.htm, 2014-04-17/2017-01-21.

Ministry of Environmental, Ministry of Land and Resources. National survey of soil pollution bulletin [EB/OL]. http://www.gov. cn/foot/2014-04/17/content_2661768.htm, 2014-04-17/2017-01-21. |

| [10] | Wei B G, Yang L S. A review of heavy metal contaminations in urban soils, urban road dusts and agricultural soils from China[J]. Microchemical Journal, 2010, 94(2): 99–107. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2009.09.014 |

| [11] | Wang G, Su M Y, Chen Y H, et al. Transfer characteristics of cadmium and lead from soil to the edible parts of six vegetable species in southeastern China[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2006, 144(1): 127–135. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2005.12.023 |

| [12] | Li P J, Wang X, Allinson G, et al. Risk assessment of heavy metals in soil previously irrigated with industrial wastewater in Shenyang, China[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2009, 161(1): 516–521. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.03.130 |

| [13] |

李小牛, 周长松, 杜斌, 冯民权. 北方污灌区土壤重金属污染特征分析[J].

西北农林科技大学学报(自然科学版), 2014, 42(6): 205–212.

Li X N, Zhou C S, Du B, Feng M Q. Pollution characteristic of heavy metals in sewage irrigated soil of Northern China[J]. Journal of Northwest A&F University (Nature Science Edition), 2014, 42(6): 205–212. |

| [14] | Sanità di Toppi L, Gabbrielli R. Response to cadmium in higher plants[J]. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 1999, 41(2): 105–130. DOI:10.1016/S0098-8472(98)00058-6 |

| [15] |

董彬. 中国土壤重金属污染修复研究展望[J].

生态科学, 2012, 31(6): 683–687.

Dong B. Research advance of soil heavy metals pollution in China[J]. Ecological Science, 2012, 31(6): 683–687. |

| [16] | Martin T A, Ruby M V. Review of in situ remediation technologies for lead, zinc and cadmium in soil [J]. Remediation Journal, 2004, 14(3): 35–53. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6831 |

| [17] | Finžgar N, Kos B, Leštan D. Bioavailability and mobility of Pb after soil treatment with different remediation methods[J]. Plant Soil and Environment, 2006, 52(1): 25–34. |

| [18] | Medina J, Guida H N. Stabilization of lateritic soils with phosphoric acid[J]. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering, 1995, 13(4): 199–216. DOI:10.1007/BF00422210 |

| [19] | Wuana R A, Okieimen F E. Heavy metals in contaminated soils: a review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation[J]. International Scholarly Research Network Ecology, 2011, : 1–20. DOI:10.5402/2011/402647 |

| [20] |

黄化刚, 李廷强, 朱治强, 等. 可溶性磷肥对重金属复合污染物土壤东南景天提取锌/镉及其养分积累的影响[J].

植物营养与肥料学报, 2012, 18(2): 382–389.

Huang H G, Li T Q, Zhu Z Q, et al. Effects of soluble phosphate fertilizer on Zn/Cd phytoextraction and nutrient accumulation of Sedum alfredii H. in co-contaminated soil [J]. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science, 2012, 18(2): 382–389. DOI:10.11674/zwyf.2012.11294 |

| [21] | Daniel-Vedele F, Krapp A, Kaiser W M. Cellular biology of nitrogen metabolism and signaling[J]. Plant Cell Monographs, 2010, 17: 145–172. DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-10613-2 |

| [22] |

缪其松, 曾后清, 朱毅勇, 等. 铵态氮营养下水稻根系分泌氢离子与细胞膜电位及质子泵的关系[J].

植物营养与肥料学报, 2011, 17(5): 1044–1049.

Miu Q S, Zeng H Q, Zhu Y Y, et al. Relationship between membrane potential, plasma membrane H+-pump and H+ release by rice root under ammonium nutrition [J]. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science, 2011, 17(5): 1044–1049. |

| [23] | Florijn P J, Nelemans J A, van Beusichem M L. The influence of the form of nitrogen nutrition on uptake and distribution of cadmium in lettuce varieties[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 1992, 15(11): 2405–2416. DOI:10.1080/01904169209364483 |

| [24] | Zaccheo P, Crippa L, Pasta V D M. Ammonium nutrition as a strategy for cadmium mobilization in the rhizosphere of sunflower[J]. Plant and Soil, 2006, 283(1-2): 43–56. DOI:10.1007/s11104-005-4791-x |

| [25] | Eriksson J E. Effects of nitrogen-containing fertilizers on solubility and plant uptake of cadmium[J]. Water, Air and Soil Pollution, 1990, 49(3-4): 355–368. DOI:10.1007/BF00507075 |

| [26] | Willaert G, Verloo M. Effects of various nitrogen fertilizers on the chemical and biological activity of major and trace elements in a cadmium contaminated soil[J]. Pédologie, 1992, 42(1): 83–91. |

| [27] | Liu W X, Zhang C J, Hu P J, et al. Influence of nitrogen form on the phytoextraction of cadmium by a newly discovered hyperaccumulator Carpobrotus rossii [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(2): 1246–1253. DOI:10.1007/s11356-015-5231-y |

| [28] | Hassan M J, Wang F, Ali S, Zhang G P. Toxic effect of cadmium on rice as affected by nitrogen fertilizer form[J]. Plant and Soil, 2005, 277(1/2): 359–365. |

| [29] | Xie H L, Jiang R F, Zhang F S, et al. Effect of nitrogen form on the rhizosphere dynamics and uptake of cadmium and zinc by the hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens [J]. Plant and Soil, 2009, 318(1/2): 205–215. |

| [30] | Hu P J, Yin Y G, Ishikawa S, et al. Nitrate facilitates cadmium uptake, transport and accumulation in the hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola [J]. Environment Science and Pollution Research, 2013, 20(9): 6306–6316. DOI:10.1007/s11356-013-1680-3 |

| [31] | Luo B F, Du S T, Lu K X, et al. Iron uptake system mediates nitrate-facilitated cadmium accumulation in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants [J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2012, 63(8): 3127–3136. DOI:10.1093/jxb/ers036 |

| [32] | Yang Y J, Xiong J, Chen R J, et al. Excessive nitrate enhances cadmium (Cd) uptake by up-regulating the expression of OsIRT1 in rice (Oryza sativa) [J]. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 2016, 122: 141–149. DOI:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.10.001 |

| [33] | Zhang R R, Liu Y, Xue W L, et al. Slow-release nitrogen fertilizers can improve yield and reduce Cd concentration in pakchoi (Brassica chinensis L.) grown in Cd-contaminated soil [J]. Environment Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(24): 25074–25083. DOI:10.1007/s11356-016-7742-6 |

| [34] | Xu R K, Zhao A Z, Yuan J H, Jiang J. pH buffering capacity of acid soils from tropical and subtropical regions of China as influenced by incorporation of crop straw biochars[J]. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2012, 12(4): 494–502. DOI:10.1007/s11368-012-0483-3 |

| [35] | Baldantoni D, Morra L, Zaccardelli M, Alfani A. Cadmium accumulation in leaves of leafy vegetables[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2016, 123: 89–94. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.05.019 |

| [36] | Shentu J L, He Z L, Yang X E, Li T Q. Accumulation properties of cadmium in a selected vegetable-rotation system of southeastern China[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2008, 56(15): 6382–6388. DOI:10.1021/jf800882q |

| [37] | Liu W T, Zhou Q X, An J, et al. Variations in cadmium accumulation among Chinese cabbage cultivars and screening for Cd-safe cultivars[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2010, 173(1-3): 737–743. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.08.147 |

| [38] | Chen X, Wang J, Shi Y, et al. Effects of cadmium on growth and photosynthetic activities in pakchoi and mustard[J]. Botanical Studies, 2011, 52: 41–46. |

| [39] |

杨芸, 周坤, 徐卫红, 等. 外源铁对不同品种番茄光合特性、品质及镉积累的影响[J].

植物营养与肥料学报, 2015, 21(4): 1006–1015.

Yang Y, Zhou K, Xu W H, et al. Effect of exogenous iron on photosynthesis, quality, and accumulation of cadmium in different varieties of tomato[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer, 2015, 21(4): 1006–1015. DOI:10.11674/zwyf.2015.0420 |

| [40] |

黄绍文, 唐继伟, 李春花. 不同栽培方式菜田耕层土壤重金属状况[J].

植物营养与肥料学报, 2016, 22(3): 707–718.

Huang S W, Tang J W, Li C H. Status of heavy metals in vegetable soils under different patterns of land use[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer, 2016, 22(3): 707–718. DOI:10.11674/zwyf.14590 |

| [41] |

鲍士旦. 土壤农化分析[M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2005.

Bao S D. Soil and agricultural chemical analysis[M]. Beijing: China Agriculture Press, 2005. |

| [42] |

鲁如坤. 土壤农业化学分析方法[M]. 北京: 中国农业科技出版社, 2000.

Lu R K. Soil agrochemistry analytical methods[M]. Beijing: Chinese Agricultural Science and Technology Press, 2000. |

| [43] |

陕红, 刘荣乐, 李书田. 施用有机物料对土壤镉形态的影响[J].

植物营养与肥料学报, 2010, 16(1): 136–144.

Shan H, Liu R L, Li S T. Cadmium fractions in soils as influenced by application of organic materials[J]. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science, 2010, 16(1): 136–144. DOI:10.11674/zwyf.2010.0120 |

| [44] | Yang X E, Long X X, Ye H B, et al. Cadmium tolerance and hyperaccumulation in a new Zn-hyperaccumulation plant species (Sedum alfredii Hance) [J]. Plant and Soil, 2004, 259(1-2): 181–189. |

| [45] | Yan H, Filardo F, Hu X T, et al. Cadmium stress alters the redox reaction and hormone balance in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) leaves [J]. Environment Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(4): 3758–3769. DOI:10.1007/s11356-015-5640-y |

| [46] |

GB/T 23739-2009. 土壤质量有效态铅和镉的测定原子吸收法[S].

GB/T 23739-2009. Soil quality-analysis of available lead and cadmium contents in soils atomic absorption spectrometry[S]. |

| [47] | Gill S S, Khan N A, Tuteja N. Differential cadmium stress tolerance in five Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L.) cultivars: an evaluation of the role of antioxidant machinery [J]. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 2011, 6(2): 293–300. |

| [48] | Mattina M J I, Lannucci-Berger W, Musante C, White J C. Concurrent plant uptake of heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants from soil[J]. Environment Pollution, 2003, 124(3): 375–378. DOI:10.1016/S0269-7491(03)00060-5 |

| [49] | Muñoz N, González C, Molina A, et al. Cadmium-induced early changes in $rm{O}_{small 2}^{overline {,cdot,}} $, H2O2 and antioxidative enzymes in soybean (Glycine max L.) leaves [J]. Plant Growth Regulation, 2008, 56: 159–166. DOI:10.1007/s10725-008-9297-0 |

| [50] |

袁波, 傅瓦利, 蓝家程, 等. 菜地土壤铅、镉有效态与生物有效性研究[J].

水土保持学报, 2011, 25(5): 130–134.

Yuan B, Fu W L, Lan J C, et al. Study on the available and bioavailability of lead and cadmium in soil of vegetable plantation[J]. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 2011, 25(5): 130–134. |

| [51] |

张攀伟, 罗金葵, 陈巍, 沈其荣. 硝铵比例影响小白菜生长和叶绿素含量的原因探究[J].

植物营养与肥料学报, 2006, 12(5): 711–716.

Zhang P W, Luo J K, Chen W, Shen Q R. Influence of NO3–: NH4+ ratio on growth and chlorophyll content in pakchoi [J]. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science, 2006, 12(5): 711–716. |

| [52] | Krupa Z. Cadmium-induced changes in the composition and structure of the light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b protein complex Ⅱ in radish cotyledons[J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 1988, 73(4): 518–524. DOI:10.1111/ppl.1988.73.issue-4 |

| [53] | Siedlecka A, BaszyńAski T. Inhibition of electron flow around photosystem Ⅰ in chloroplasts of Cd-treated maize plants is due to Cd-induced iron deficiency[J]. Physiologia Plantarum, 1993, 87(2): 199–202. DOI:10.1111/ppl.1993.87.issue-2 |

| [54] | Fornazier R F, Ferreira R R, Vitória A P, et al. Effect of cadmium on antioxidant enzyme activities in sugar cane[J]. Biologia Plantarum, 2002, 45(1): 91–97. DOI:10.1023/A:1015100624229 |

| [55] | Cho U H, Park J O. Mercury-induced oxidative stress in tomato seedlings[J]. Plant Science, 2000, 156(1): 1–9. DOI:10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00227-2 |

| [56] | Malecka A, Jarmuszkiewicz W, Tomaszewska B. Antioxidative defense to lead stress in subcellular compartments of pea root cells[J]. Acta Biochimica Polonica, 2001, 48(3): 687–698. |

| [57] | Yu H, Wang J L, Fang W, et al. Cadmium accumulation in different rice cultivars and screening for pollution-safe cultivars of rice[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2006, 370(2/3): 302–309. |

| [58] | Tsadilas C D, Karaivazoglou N A, Tsotsolis N C, et al. Cadmium uptake by tobacco as affected by liming, N form, and year of cultivation[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2005, 134(2): 239–246. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2004.08.008 |

| [59] | Sarwar N, Saifullah S S, et al. Role of mineral nutrition in minimizing cadmium accumulation by plants[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2010, 90(6): 925–937. |

| [60] | Havlin J L, Beaton J D, Tisdale S L, Nelson W R. Soil fertility and fertilizers: an introduction to nutrient management[M]. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1999. |

| [61] | Marschner H. Mineral nutrition of higher plants (2nd edition)[M]. London: Academic Press, 1995. |

| [62] | Lorenz S E, Hamon R E, McGrath S P, et al. Application of fertilizer cations affect cadmium and zinc concentrations in soil solutions and uptake by plants[J]. European Journal of Soil Science, 1994, 45(2): 159–165. DOI:10.1111/ejs.1994.45.issue-2 |

| [63] | Xian X F, Shokohifard G I. Effect of pH on chemical forms and plant availability of cadmium, zinc, and lead in polluted soils[J]. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 1989, 45(3/4): 265–273. |

| [64] | Guttormsen G, Singh B R, Jeng A S. Cadmium concentration in vegetable crops grown in a sandy soil as affected by Cd levels in fertilizer and soil pH[J]. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 1995, 41(1): 27–32. |

| [65] | Valdez-González J C, López-Chuken U J, Guzmán-Mar J L, et al. Saline irrigation and Zn amendment effect on Cd phytoavailability to Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris L.) grown on a long-term amended agricultural soil: a human risk assessment [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2014, 21(9): 5909–5916. DOI:10.1007/s11356-014-2498-3 |

| [66] | Mao Q Q, Guan M Y, Lu K X, et al. Inhibition of nitrate transporter 1.1-controlled nitrate uptake reduces cadmium uptake in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Physiology, 2014, 166(2): 934–944. DOI:10.1104/pp.114.243766 |

2017, Vol. 23

2017, Vol. 23  doi:

doi: