文章信息

- 李蕙伊, 刘畅, 赵洋子, 曾仁庆, 甘淼, 王涛, 于诗源, 崇巍

- LI Huiyi, LIU Chang, ZHAO Yangzi, ZENG Renqing, GAN Miao, WANG Tao, YU Shiyuan, CHONG Wei

- 急诊科成人创伤患者院内死亡危险因素分析

- Analysis of the Risk Factors of In-hospital Death in Adult Trauma Patients at the Emergency Department

- 中国医科大学学报, 2018, 47(2): 128-131

- Journal of China Medical University, 2018, 47(2): 128-131

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2017-08-18

- 网络出版时间:2018-01-08 10:54

2. 中国医科大学附属盛京医院急诊科, 沈阳 110004;

3. 中山大学医学院附属肿瘤医院神经外科, 广州 510080

2. Department of Emergency Medicine, Shengjing Hospital, China Medical University, Shenyang 110004, China;

3. Department of Neurosurgery, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510080, China

创伤是40岁以下人群的首要死亡原因[1]。识别影响急诊科成人创伤患者死亡的危险因素,有助于提高创伤患者的救治质量。目前,损伤严重程度评分(injury severity score,ISS)被认为是描述创伤严重程度的“金标准” [2]。ISS从解剖学方面评估人体创伤情况,与创伤严重度有较好的相关性,国内外被广泛应用[3-4]。其不足之处是没有考虑系统和脏器的功能状态[5]。序贯器官衰竭(sequential organ failure assessment,SOFA)评分[6]是对6个主要脏器或系统功能进行评估。许多临床研究[7]发现,早期创伤患者的死亡与SOFA评分有关。格拉斯哥昏迷评分(Glasgow coma scale,GCS)根据睁眼、语言和运动3个方面的功能进行评分,是评价脑外伤患者预后的重要评分,对院前或院内创伤患者预后的评估很有价值[8]。本研究以急诊科成人创伤患者为对象,对患者解剖损伤与脏器功能的临床资料进行分析,探讨急诊科成人创伤患者院内死亡的危险因素。

1 材料与方法 1.1 一般资料选取2016年8月至2017年2月中国医科大学附属第一医院急诊科就诊的86例创伤患者为研究对象,其中,男58例,女28例,年龄19~92岁。参考国内外研究[6, 9],纳入标准:(1)年龄≥18岁;(2)受伤到来院时间≤24 h,且伤后未进行过手术。排除标准:(1)临床资料不全;(2)放弃治疗或抢救。纳入患者中,交通事故伤56例(65.1%),摔伤11例(12.8%),高空坠落伤9例(10.5%),刀刺伤3例(3.5%),钝器伤3例(3.5%),爆震伤2例(2.3%),掩埋挤压伤2例(2.3%)。

1.2 研究指标及分组记录患者的年龄、性别、来诊时生命体征、SpO2、GCS、ISS、SOFA评分、血红蛋白(hemoglobin,Hb)、外周血白细胞计数(white blood cell,WBC)、谷丙转氨酶(alanine aminotransferase,ALT)、总胆红素(total bilirubin,TBil)、血清白蛋白(albumin,ALB)、血清尿素氮(blood urea nitrogen,BUN)、血清肌酐(creatinine,Cr)、凝血酶原时间(prothrombin time,PT)、活化部分凝血活酶时间(activated partial thromboplastin time,APTT)、纤维蛋白原(fibrinogen,Fg)等指标。根据在院期间是否死亡分为存活组和死亡组,存活组74例,死亡组12例。

1.3 统计学分析采用SPSS 22.0软件进行统计学分析。正态分布的计量资料以x± s表示,组间比较采用t检验;非正态分布的计量资料以中位数(四分位数间距)表示,组间比较采用非参数秩和检验;计数资料的组间比较采用χ2检验;按P < 0.1,筛选出2组差异显著的指标,将其纳入logistic回归,得出院内死亡的独立危险因素,绘制这些因素与院内死亡关系的受试者工作曲线(receiver operating characteristic,ROC),评估其对院内死亡的预测效能。

2 结果 2.1 创伤患者死亡相关因素的单因素分析结果显示,SOFA评分、ISS、HR、WBC、Cr、BUN、PT和APTT显著高于存活组(P < 0.1);GCS、MAP、SpO2、PLT、Hb、ALB和Fg显著低于存活组(P < 0.1);2组性别、年龄、ALT、TBil均无统计学差异(P > 0.1),见表 1。

| Factor | Survival group (n = 72) | Non-survival group (n = 14) | P |

| Age (year) | 49.04±17.13 | 53.07±19.27 | 0.432 |

| Gender [n (%) ] | |||

| Male | 45 (62.5) | 13 (92.9) | 0.188 |

| Female | 27 (37.5) | 1 (7.1) | |

| MAP (mmHg) | 97.9±17.46 | 88.4±18.76 | 0.070 |

| SpO2 (%) | 98 (96-99) | 95 (93-99) | 0.056 |

| HR (beat/min) | 83.5 (76.00-100.00) | 114.5 (85.75-140.75) | 0.025 |

| GCS | 15 (15-15) | 3 (3-7) | < 0.001 |

| SOFA | 0 (0.00-2.00) | 8.5 (6.00-9.25) | < 0.001 |

| ISS | 10.5 (4.00-19.00) | 16.5 (12.75-25.00) | 0.079 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.61 (4.65-7.25) | 6.55 (5.95-7.43) | 0.038 |

| PLT (×109) | 207.7±69.48 | 165.42±69.48 | 0.041 |

| ALT (U/L) | 37.5 (23.5-76.0) | 49.5 (31.0-60.7) | 0.183 |

| Hb (g/L) | 127.65±23.23 | 104.57±34.73 | 0.019 |

| WBC (×109) | 10.91 (8.50-14.52) | 14.56 (10.47-19.74) | 0.088 |

| TBil (μmol/L) | 13.5 (11.00-18.45) | 13.25 (8.88-18.18) | 0.734 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 59.5 (53.0-71.0) | 93.5 (63.5-134.5) | 0.005 |

| ALB (g/L) | 38.2 (33.45-41.30) | 26.85 (13.90-41.15) | 0.007 |

| PT (s) | 14 (13.5-15.1) | 17.4 (14.9-24.2) | 0.001 |

| APTT (s) | 34.55 (32.63-56.40) | 46.85 (33.35-56.40) | < 0.001 |

| Fg (g/L) | 2.96 (2.35-4.21) | 1.58 (0.88-2.47) | 0.001 |

| The measurement data with Gaussian distribution were described with mean±standared deviation, and those with abnormal distribution were described with median (quartile range). | |||

2.2 创伤患者死亡危险因素logistic回归分析

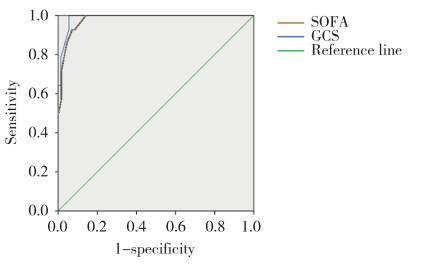

筛选出2组差异显著的指标,将其纳入logistic回归。将性别、年龄、MAP、SpO2、HR、ISS、BUN、PLT、Hb、WBC、Cr、ALB、PT、APTT、Fg和GCS纳入logistic回归,得出GCS(β=-0.957,OR=0.384,P = 0.012)为患者院内死亡的独立危险因素;将性别、年龄、HR、ISS、BUN、Hb、WBC、ALB、PT、APTT、Fg和SOFA评分纳入logistic回归,得出SOFA评分(β=0.966,OR = 2.627,P < 0.001)为患者院内死亡的独立危险因素,见表 2、3。GCS和SOFA评分的ROC曲线下面积分别为0.989和0.982,2者对院内死亡的预测效能好,见图 1。

| Factor | β | OR | P |

| Gender | -8.469 | < 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Age | 0.052 | 1.053 | 0.259 |

| GCS | -0.957 | 0.384 | 0.012 |

| Factor | β | OR | P |

| Gender | -51.714 | < 0.001 | 0.993 |

| Age | -0.062 | 0.940 | 0.221 |

| SOFA | 0.966 | 2.627 | < 0.001 |

|

| 图 1 急诊科院内死亡独立危险因素的ROC曲线 Fig.1 ROC of the independent risk factors of in-hospital death at the emergency department |

3 讨论

本研究发现,GCS和SOFA评分是急诊科成人创伤患者院内死亡的独立危险因素,提示创伤患者就诊时的脏器功能状态(尤其是脑功能状态)与预后关系密切。GCS能很好地预测相关脑创伤结局(是否急诊机械通气、脑外科手术、脑损伤程度、死亡)[10]。GCS评分越低,伤情越重,病死率越高。GCS评分对创伤患者治疗和分级有价值[11]。YOUSEFZADEHCHABOK等[12]分析了588例创伤儿童,发现GCS与儿童创伤评分(pediatric trauma score,PTS)和ISS比较,能更好预测创伤儿童的死亡。过去脑外伤和出血仍然是导致创伤患者死亡的主要原因[13]。近年来OYENIYI等[14]研究发现,由于出血的问题得到了有效控制,脑外伤成为创伤患者死亡的主要原因。

SOFA评分 > 3分一般认为是严重器官功能衰竭[15]。SOFA评分对预测院内脓毒症死亡率有很高价值[16]。SOFA评分也可以通过对创伤患者脏器功能衰竭的描述来评估其死亡风险[17-18]。近期JAWA等[19]研究发现快速SOFA评分(包括GCS、收缩压、呼吸频率)也是急诊钝性伤患者死亡的独立危险因素,快速SOFA评分越高,不良结局事件发生率越高。临床研究[7]发现早期创伤患者的死亡与SOFA评分有关。本研究结果显示,SOFA评分对急诊科创伤患者的死亡同样具有预测价值,提示创伤患者来诊时脏器和系统的功能状态对预后有重要的影响,与以往的研究结果一致。

ISS是将全身分为6个区域:头颈部、面部、胸部、腹部或盆腔脏器、四肢或骨盆、体表。在3个损伤最严重的ISS身体区域中,各选出1个最高AIS分值,将它们分别平方,然后将3个平方值相加即为ISS [20]。≥16分认为严重创伤[3]。在本研究中ISS对创伤患者预后效果一般。CHAWDA等[5]研究指出,仅仅通过解剖描述不足以预测创伤患者的结局。因此,大多数观点认为对创伤的描述应该包括解剖学和生理学两个方面,而SOFA评分和GCS是对创伤患者生理情况的描述,能更好反映预后。

综上所述,SOFA评分和GCS均为急诊创伤患者院内死亡的独立危险因素,提示创伤患者来诊时的脏器功能状态(尤其是脑功能状态)与其预后关系密切。因此对于创伤患者,生理指标的评估对其院内死亡预测的价值可能更大。本研究属于回顾性研究,样本量较小。今后将扩大样本量进行前瞻性研究,有望建立急诊科兼顾解剖损伤和生理功能且可靠的评估成人创伤患者病情严重程度的评分系统。

| [1] |

OVEIS S, ASHKAN TDS, SHOJAEDDIN NS, et al. A new injury severity score for predicting the length of hospital stay in multiple trauma patients[J]. Trauma Mon, 2016, 21(1): e20349. DOI:10.5812/traumamon.20349 |

| [2] |

DENG Q, TANG B, XUE C, et al. Comparison of the ability to predict mortality between the injury severity score and the new injury severity score:a meta-analysis[J]. Int J Enviro Res Pub Health, 2016, 13(8): 825. DOI:10.3390/ijerph13080825 |

| [3] |

PAFFRATH T, LEFERING R, FLOH S. How to define severely injured patients?-An injury severity score (ISS) based approach alone is not sufficient[J]. Injury, 2014, 45(Suppl 3): S64. DOI:10.1016/j.injury.2014.08.020 |

| [4] |

ALBERDI F, GARCÍA I, ATUTXA L, et al. Epidemiology of severe trauma[J]. Med Intensiva, 2014, 38(9): 580-588. DOI:10.1016/j.medin.2014.06.012 |

| [5] |

CHAWDA MN, HILDEBRAND F, PAPE HC, et al. Predicting outcome after multiple trauma:which scoring system?[J]. Injury, 2004, 35(4): 347-358. DOI:10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00140-2 |

| [6] |

VOGEL JA, LIAO MM, HOPKINS E, et al. Prediction of postinjury multiple-organ failure in the emergency department:development of the denver emergency department trauma organ failure score[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2014, 76(1): 140-145. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182a99da4 |

| [7] |

FUEGLISTALER P, AMSLER F, SCHÜEPP M, et al. Prognostic value of sequential organ failure assessment and simplified acute physiology ii score compared with trauma scores in the outcome of multiple-trauma patients[J]. Am J Surg, 2010, 200(2): 204-214. DOI:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.035 |

| [8] |

KERBY JD, MACLENNAN PA, BURTON JN, et al. Agreement between prehospital and emergency department glasgow coma scores[J]. J Trauma, 2007, 63(5): 1026. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e318157d9e8 |

| [9] |

TRANCĂ S, PETRIOR C, HAGĂU N, et al. Can APACHEⅡ, SOFA, ISS, and RTS severity scores be used to predict septic complications in multiple trauma patients?[J]. J Critical Care Med, 2016, 2(3): 124-130. DOI:10.1515/jccm-2016-0019 |

| [10] |

GILL M, STEELE R, WINDEMUTH R, et al. A comparison of five simplified scales to the out-of-hospital Glasgow coma scale for the prediction of traumatic brain injury outcomes[J]. Acad Emerg Med, 2006, 13(9): 968-973. DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2006.05.019 |

| [11] |

LECKY F, WOODFORD M, EDWARDS A, et al. Trauma scoring systems and databases[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2014, 113(2): 286-294. DOI:10.1093/bja/aeu242 |

| [12] |

YOUSEFZADEHCHABOK S, KAZEMNEJADLEILI E, KOUCHAKINEJADERAMSADATI L, et al. Comparing pediatric trauma, glasgow coma scale and injury severity scores for mortality prediction in traumatic children[J]. Turkish J Trauma Emerg Surg, 2016, 22(4): 328. DOI:10.5505/tjtes.2015.839 |

| [13] |

DUTTON RP, STANSBURY LG, LEONE S, et al. Trauma mortality in mature trauma systems:are we doing better? An analysis of trauma mortality patterns, 1997-2008[J]. J Trauma, 2010, 69(3): 620. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181bbfe2a |

| [14] |

OYENIYI BT, FOX EE, SCERBO M, et al. Trends in 1029 trauma deaths at a level 1 trauma center:impact of a bleeding control bundle of care[J]. Injury, 2017, 48(1): 5-12. DOI:10.1016/j.injury.2016.10.037 |

| [15] |

ATLE U, REIDAR K, TORE WL, et al. Multiple organ failure after trauma affects even long-term survival and functional status[J]. Critical Care, 2007, 11(5): 1-8. DOI:10.1186/cc6111 |

| [16] |

JONES AE, TRZECIAK S, KLINE JA. The sequential organ failure assessment score for predicting outcome in patients with severe sepsis and evidence of hypoperfusion at the time of emergency department presentation[J]. Crit Care Med, 2009, 37(5): 1649. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819def97 |

| [17] |

ÑAMENDYSSILVASA, SIlVAMEDINAMA, VÁSQUEZBARA-HONAGM, 等. Application of a modified sequential organ failureassessment score to critically ill patients[J]. Brazilian J Med Biol Res, 2013, 46(2): 186-193. DOI:10.1590/1414-431X20122308 |

| [18] |

SAFARI S, SHOJAEE M, RAHMATI F, et al. Accuracy of SOFA score in prediction of 30-day outcome of critically ill patients[J]. Turkish J Emerg Med, 2016, 16(4): 146-150. DOI:10.1016/j.tjem.2016.09.005 |

| [19] |

JAWA RS, VOSSWINKEL JA, MCCORMACK JE, et al. Risk assessment of the blunt trauma victim:the role of the quick sequential organ failure assessment score (qSOFA)[J]. Am J Surg, 2017, 214(3): 397. DOI:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.05.011 |

| [20] |

VADOOD N, IRAJ F, SOODABE V, et al. Calculation of the probability of survival for trauma patients based on trauma score and the injury severity score model in Fatemi hospital in Ardabil[J]. Arch Trauma Res, 2013, 2(1): 30-35. DOI:10.5812/atr.9411 |

2018, Vol. 47

2018, Vol. 47